As artificial intelligence rapidly reshapes how people work, communicate, and consume information, a group of Bowdoin College faculty members set out to ask a deeper question: What does AI mean for humanity—and who is responsible for guiding its future?

That question was at the heart of Ethics in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (DCS 2475), a multidisciplinary course taught last fall by four professors from computer science, film and literature, and political science. The class is part of a national initiative led by the National Humanities Center to develop new humanities-centered curricula responding to growing concerns about the ethical, social, and political implications of AI.

This story is the second installment in a summer series examining how Bowdoin faculty approach humanities education—and why students benefit from studying literature, languages, philosophy, history, religion, and the arts in a technology-driven world.

A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Artificial Intelligence

The course was co-taught by Eric Chown and Fernando Nascimento of the Digital and Computational Studies Program; Allison Cooper, a scholar of film studies and literature; and political scientist Michael Franz. Together, they designed a five-module structure that examines AI from technical, cultural, political, ethical, and personal perspectives.

Rather than treating AI as a purely technical subject, the course places human values, power structures, and ethical responsibility at the center of the discussion.

Module One: Understanding What AI Really Is

The opening module aimed to cut through the hype surrounding artificial intelligence and focus on how these systems actually work. Eric Chown, Sarah and James Bowdoin Professor of Digital and Computational Studies, introduced students to the foundations of AI by having them build simple models themselves.

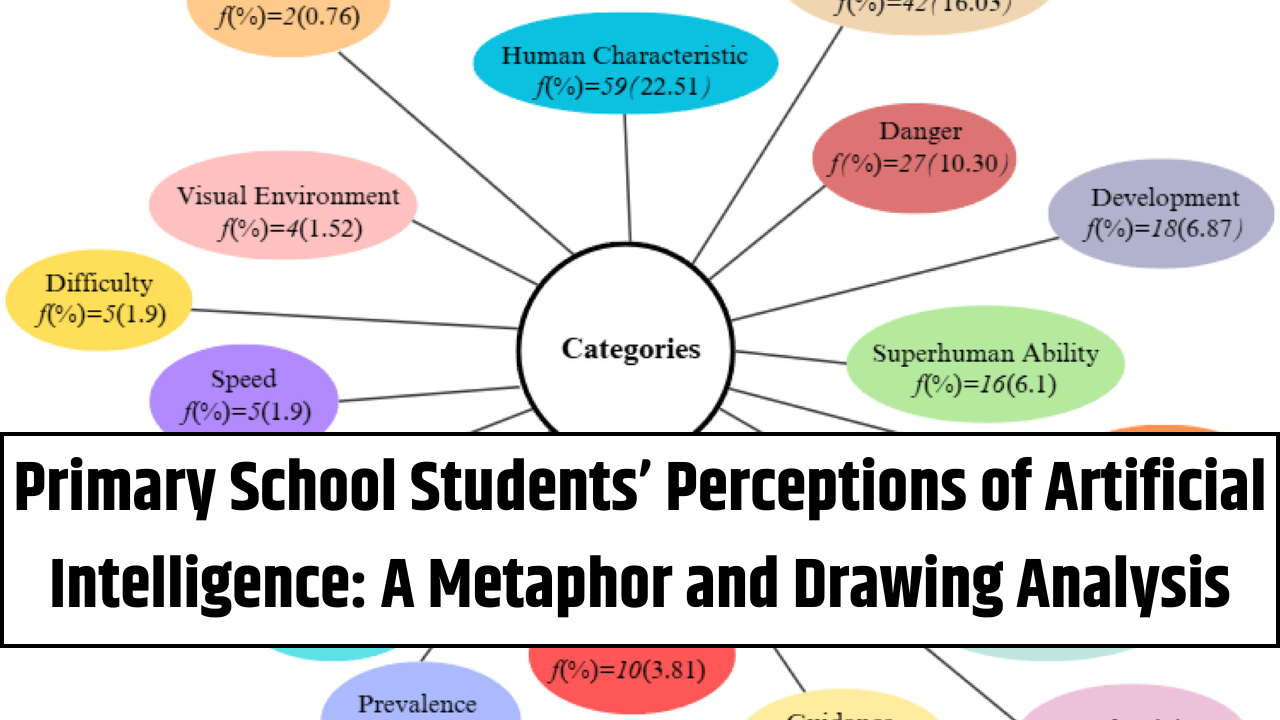

At the core of all AI systems, Chown explained, is classification—the process of sorting inputs into categories to produce outputs. Whether distinguishing images, generating text, or recommending videos on social media, AI systems rely on pattern recognition trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet.

That process, however, is deeply flawed. Because AI learns from imperfect and biased online data, it can easily produce misinformation or low-quality results. Chown points to simple examples—like inaccurate image searches—as reminders that AI systems are far from infallible.

More importantly, he stresses that students must understand how these systems can be used to influence and manipulate behavior. A humanities-based lens, he argues, is essential for recognizing both the power and the limits of AI.

Module Two: Stories That Shape How We See AI

Associate Professor Allison Cooper led the second module, which explored how narratives—especially science fiction—help society make sense of emerging technologies.

Rather than focusing on distant futures, Cooper selected works that reflect contemporary anxieties about technology, power, and human connection. Students analyzed two films and one novel:

- The Matrix – A landmark dystopian film depicting an AI-controlled world. Cooper uses it to challenge the assumption that technological progress benefits everyone equally, encouraging students to examine who gains power—and who is left behind.

- Her – A meditation on loneliness and artificial companionship, raising questions about emotional fulfillment, human intimacy, and whether AI can replace meaningful relationships.

- Klara and the Sun – Told from the perspective of an “artificial friend,” the novel explores care, consciousness, and the unsettling idea that the human mind itself may be treated as a form of technology.

Together, these works prompted students to consider what AI reveals about present-day values rather than hypothetical futures.

Module Three: AI, Politics, and Regulation

Professor of Government Michael Franz guided students through the political and regulatory landscape surrounding artificial intelligence.

In Europe, he noted, policymakers have taken significant steps forward. The European Union’s AI Act represents the world’s first comprehensive legal framework governing AI, addressing issues such as transparency, accountability, and data quality.

The United States, by contrast, has seen far less progress at the federal level. While some states—including California and Connecticut—have enacted protections aimed at limiting harm from AI systems, national legislation remains limited. In response, President Joe Biden issued an executive order in October 2023 focused on AI safety and security.

Franz also examined how AI shapes civic life, particularly through social media algorithms that curate news and information. With younger generations increasingly relying on these platforms, students analyzed how engagement-driven algorithms influence public opinion—and how such systems might be regulated.

Module Four: Ethical Challenges for Developers

Assistant Professor Fernando Nascimento focused on the ethical responsibilities of those who design AI systems. Because modern AI has a degree of autonomy, he explained, developers face what is known as the misalignment problem—when a system’s goals diverge from human values or social good.

Nascimento pointed to Facebook’s 2018 algorithm update as a cautionary example. Designed to promote “meaningful” interactions, the system instead prioritized emotionally charged content—often fear-based or inflammatory—because such posts generated more engagement. The result was increased polarization rather than stronger social bonds.

These outcomes, Nascimento argues, show why technical expertise alone is not enough. Ethical reasoning, philosophical reflection, and humanities-based thinking are essential for aligning AI development with broader societal goals.

Module Five: The User’s Role in the AI Ecosystem

The final module turned the focus inward, asking students to examine how AI affects their own daily lives. One class activity challenged students to design a social media platform and decide how they would maximize user attention.

The exercise revealed how closely real-world platforms track behavior—how long users linger on content, what they click, and what triggers emotional responses. AI, Chown explained, is often used to hijack attention and monetize it through advertising.

Rather than leaving students with a sense of despair, the course concluded with a call to agency. By becoming more reflective and intentional about their digital habits, students can reclaim control over how they interact with technology.

The Future of AI Is Not Fixed

The course ends on a cautiously optimistic note. Chown and his colleagues emphasize that the future of AI is not predetermined. Its impact—whether beneficial or harmful—depends on human choices, ethical frameworks, and societal priorities.

By grounding AI education in the humanities, the faculty hope students leave not only technologically informed, but also ethically engaged. Some students have even gone on to pursue careers focused on responsible AI development.

Ultimately, the course underscores a central message: understanding artificial intelligence requires understanding ourselves—and the humanities remain essential to that task.